There is a moment many endurance athletes recognize instantly. You are halfway through a session that, on paper, should be manageable. You know the pace. You have done it before. Yet today everything feels heavier. Not dramatic. Not painful. Just dull. The legs respond slowly, the mind feels flat, and the effort seems strangely high for the speed you are producing.

You finish the workout anyway. You always do. And later, looking at the data, everything seems acceptable. Distance completed. Session checked. Another brick added to the wall.

But something is missing.

I have seen this pattern again and again in endurance athletes. Runners. Orienteers. Triathletes. Highly committed people who train often, rarely skip sessions, and pride themselves on discipline. From the outside, they look consistent. From the STRAVA, they look amazing. From the inside, they are slowly accumulating something that is hard to define but impossible to ignore.

They are not failing to train hard. They are failing to absorb the training.

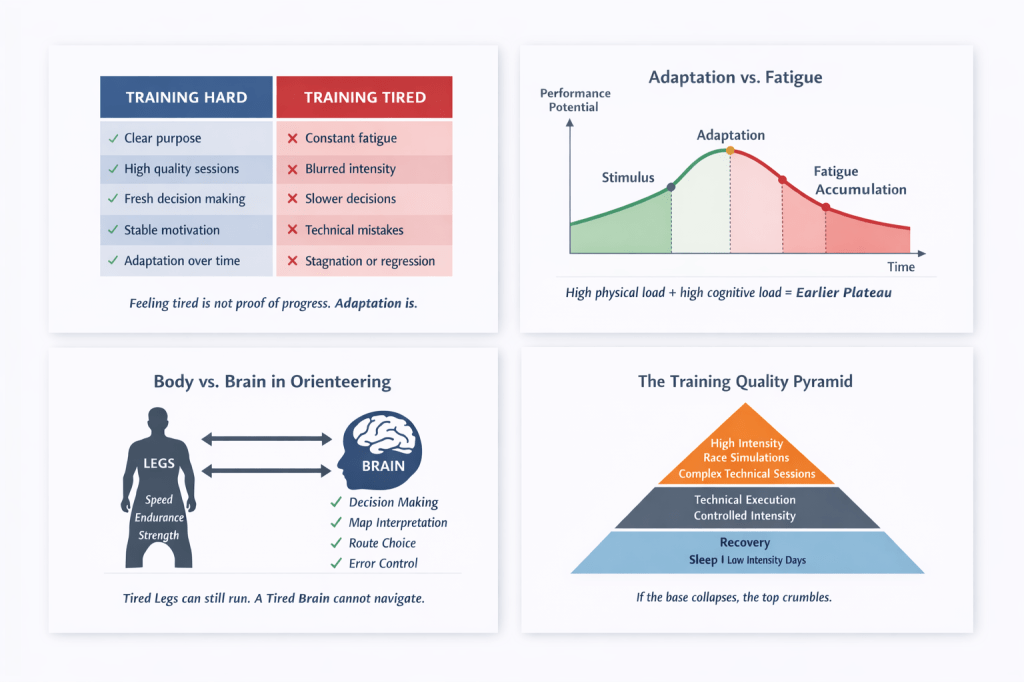

This is where many athletes get stuck. They confuse fatigue with progress. They assume that feeling tired means the work is effective. Yet adaptation does not come from exhaustion. It comes from the body and the brain having enough space to respond to the stress imposed.

When that space disappears, training becomes maintenance at best, and erosion at worst.

The tricky part is that training tired rarely feels dramatic. There is no sudden breakdown. No clear injury. Instead, quality erodes quietly. Intervals lose sharpness. Technical decisions take longer and are suboptimal. Easy runs stop feeling easy. Motivation fades not because the athlete is lazy, but because the system is overloaded.

In orienteering, this becomes even more visible. I have watched athletes who are physically strong struggle to execute simple legs on a map. They hesitate. They struggle to keep the focus on. They “disconnect suddently”. They choose safe routes when offensive ones are obvious. They drift on bearings they would normally hold cleanly. Nothing is catastrophically wrong. Everything is just slightly off.

That is fatigue speaking through the brain.

Modern research supports what many experienced coaches have observed for years. Mental and physical fatigue interact. When accumulated fatigue is high, perception of effort increases, decision making slows, and performance drops even when physiological capacity is unchanged. This has been clearly demonstrated in endurance contexts by Marcora and colleagues, who showed that mental fatigue alone can impair physical performance without changes in muscle function or cardiovascular capacity (Marcora et al., 2009).

This matters deeply for sports like orienteering, where performance depends not only on how fast you can run, but on how well you can think while running.

The common reaction to stagnation is predictable. Do more. Add volume. Add intensity. Add one more session because the body surely just needs a stronger stimulus. I have seen athletes increase training load precisely when their ability to absorb it is already compromised. The result is rarely improvement. More often, it is a deeper hole.

What is missing is not work ethic. It is clarity.

Hard training is not defined by how tired you feel at the end of the week. It is defined by whether the stimulus is clear and whether recovery is sufficient to allow adaptation. Research on overreaching and overtraining has consistently shown that performance declines when stress outweighs recovery for prolonged periods, even in well trained athletes (Meeusen et al., 2013).

The athletes who improve most over time are often not the ones who train the most hours, but the ones who protect quality. They allow hard sessions to be truly hard, and easy days to be truly easy. They resist the temptation to turn every session into a moderate struggle.

In orienteering, this balance becomes even more critical. Physical fatigue can be tolerated. Cognitive fatigue is far less forgiving. When the brain is overloaded, mistakes appear even in terrain that should feel routine. Training camps, dense competition periods, and blocks with high technical demand accumulate mental stress quickly. If recovery is not respected, athletes may feel fit while racing poorly.

Studies on training load monitoring emphasize that subjective measures such as perceived fatigue, motivation, and mental freshness often reveal overload earlier than performance metrics alone (Halson, 2014). Ignoring those signals does not make them disappear. It only delays the consequences.

What I have learned from watching many athletes over time is this. Sustainable progress is rarely built on constant pressure. It is built on rhythm. Stress followed by space. Focus followed by release. Intensity placed deliberately, not everywhere.

The most successful athletes develop an internal filter. They can tell the difference between productive discomfort and empty fatigue. They know when to push and when to step back, not because they are cautious, but because they understand that adaptation is the real goal.

If your training leaves you constantly tired, constantly flat, and constantly waiting for things to click, the answer is rarely more work. The answer is better timing, clearer intent, and deeper respect for recovery.

Your potential does not live at the edge of exhaustion.

It lives where stress is absorbed, skills stay sharp, and both body and mind are allowed to adapt.

The question is not whether you are working hard enough. The real question is whether your training is still working for you.

.

Ten Principles to Stay Ahead of Fatigue and Train with Clarity

- Understand that fatigue is not the enemy, but chronic fatigue is.

Training stress is necessary. Living in a constant state of exhaustion is not. The goal is not to avoid fatigue, but to manage it so adaptation can occur. - Monitor quality before quantity.

Volume is easy to count. Quality is harder to assess, but far more informative. When pace, precision, or decision making start to fade, fatigue is already present, even if weekly mileage looks impressive. - Respect easy days as much as hard sessions.

Easy training is not wasted time. It is where recovery, consolidation, and long-term consistency are built. Turning easy days into moderate struggles is one of the fastest ways to accumulate hidden fatigue. - Be alert to early warning signs.

Poor sleep, loss of motivation, unusually high perceived effort, recurring small aches, or declining technical sharpness are not weaknesses. They are signals. Ignoring them does not make you tougher. It makes you less adaptable. - Separate physical load from cognitive load when possible.

Especially in orienteering, stacking hard physical sessions with demanding technical work day after day overloads the system quickly. The brain also needs recovery, even if the legs feel capable. - Do not rely on tapering to fix months of overload.

Maintaining very high training loads for long periods while hoping that a short taper will magically restore freshness is a risky strategy. In practice, it often leads to flat performances, persistent fatigue, or injury rather than peak form. - Periodize with intention, not with fear of losing fitness.

Well-designed variation in load is not a loss of consistency. It is what allows consistency over years. Periodization is not about doing less, but about stressing the right systems at the right time. - Avoid becoming obsessed with weekly numbers.

Kilometers, hours, and sessions are tools, not goals. Obsession with volume often replaces honest evaluation of how the athlete is actually responding to the training. - Accept that self perception is always incomplete.

Athletes live inside the training process. That makes them committed, but also biased. Fatigue distorts judgment. What feels normal from the inside can look clearly excessive from the outside. - Value external guidance and long-term perspective.

A coach provides more than sessions. They provide context, pattern recognition, and emotional distance from daily fluctuations. That external view is often what prevents small problems from becoming long-term stagnation or recurring injuries.

Final thought

Training hard without absorbing the load leads nowhere. Sustaining very high training volumes for long periods while relying on a short taper to restore freshness is a high-risk strategy that more often produces injuries, stagnation, and flat performances than peak form.

Periodization is not optional. Fitness must be built, consolidated, and refreshed if it is to be usable when it matters. A taper can sharpen performance, but it cannot repair months of accumulated fatigue.

Because athletes operate inside their own training bubble, fatigue often distorts perception and judgment. External guidance provides clarity, long-term perspective, and timely correction.

The goal is not maximum training. The goal is maximum adaptation.

references

Marcora S, Staiano W, Manning V. Mental fatigue impairs physical performance in humans. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2009.

Meeusen R et al. Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of the Overtraining Syndrome. European Journal of Sport Science. 2013.

Halson S. Monitoring training load to understand fatigue in athletes. Sports Medicine. 2014.

Soligard T et al. How much is too much? The IOC consensus statement on load in sport and risk of injury. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2016.

Discover more from Orienteering Coach

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.